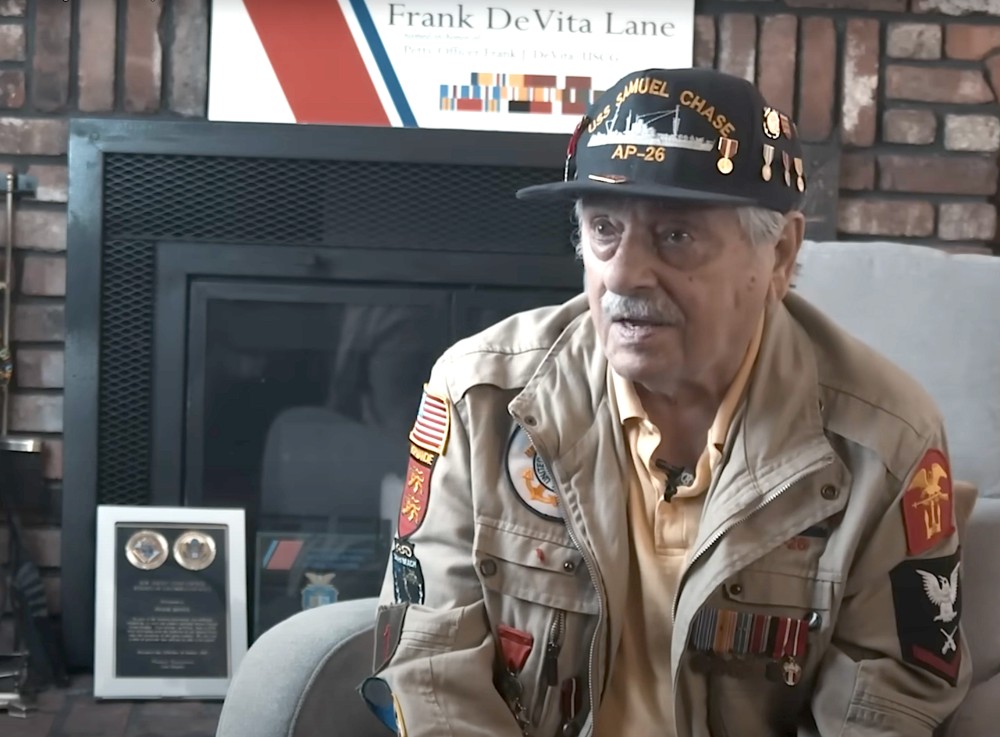

HOBOKEN — Frank DeVita had an early start 80 years ago on June 6, 1944, in the choppy waters near Normandy, France.

Saltwater splashed the Coast Guard gunner from Bensonhurst as his “Higgins” landing boat bounced on waves enroute to the beach codenamed “Omaha.” Soldiers of the Army’s 1st Infantry Division — “The Big Red One” — retched with seasickness, spraying DeVita with their breakfast.

Then, about 200 yards from shore, German machine guns swept the masses of Higgins boats, and clawed at their wooden sides.

Each boat’s ramp was armored and deflected bullets like a poncho sheds rain. It was DeVita’s job to lower the huge metal door to deploy the infantrymen. But when that order came, he paused.

“I didn’t want to die,” DeVita said in a 2020 interview with the American Veterans Center.

The coxswain piloting the Higgins barked at DeVita, “Drop the —— ramp!”

He obeyed, and nearly 30 soldiers fell dead, riddled with German slugs.

Their splattered blood mingled with the vomit, seawater, and wood splinters already clinging to DeVita.

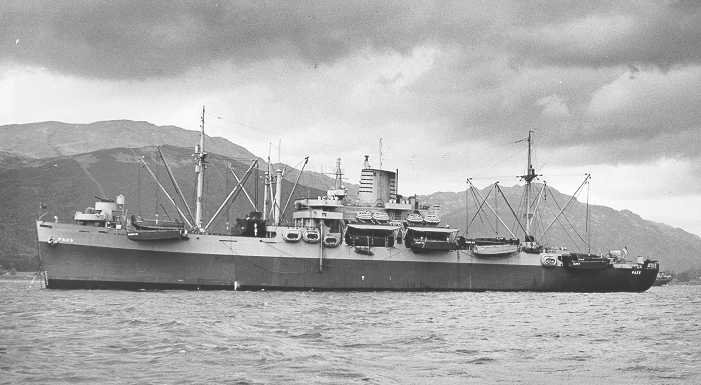

It was about 7 a.m. DeVita would be in this fight for another 16 hours. He was 19, and a Coast Guard Gunner’s Mate 3rd class on the attack transport, USS Samuel Chase.

His regular job was manning 20mm anti-aircraft guns, but one of the ship’s 26 Higgins crews was short a man. So, he became the substitute ramp controller on the first attack wave to Omaha Beach.

DeVita wanted to stay on the Samuel Chase. Still, he couldn’t stand the thought of another “Coastie” dying in his place. He made 15 trips to and from Omaha Beach; the last ones to collect many of the 2,400 men who died.

The Samuel Chase headed back across the English Channel at about 11 p.m. to its base at Southampton. He recalled saying to himself, “What the hell just happened? And how come I’m still alive?”

DeVita said he turned and saw the 208 dead soldiers on deck, shroud in body bags, and stacked “like a cord of wood.”

“I started to cry,” he said, again choking back tears.

Two months later the Samuel Chase, with DeVita aboard, delivered troops in Operation Dragoon — the allied invasion of Southern France.

In early 1945, the ship sailed to the Pacific Theater, where DeVita served in the final operations of the war, including the Battle of Okinawa.

No one was home when he arrived in Bensonhurst to see his family. A neighbor said his mother, Elizabeth, was at St. Finbar Church in nearby Bath Beach rolling cotton bandages for the war effort.

DeVita sprinted to the church. His mother saw him and fainted, DeVita said, this time with a chuckle.

After the war, DeVita returned to St. Finbar, this time to marry his lifelong neighborhood sweetheart, Dorothy Guardino, in 1948.

He became a pattern maker in the New York fashion industry. They moved to Newark, but later settled about 30 miles away in Bridgewater.

The DeVitas raised three children “in the Catholic tradition,” their youngest son, Richard, said.

Growing up, the kids — including sister Elizabeth and brother Frank — knew their dad served at Normandy, but he hedged on details, Richard said.

“He said, ‘It was hell,’” Richard recalled. “And, ‘Why would I want to bring you into such a dark place?’

“But dad had PTSD. And dad had survivor’s guilt.”

Their mother, who died in 2013, supported him emotionally, but she, too, didn’t share much with their children.

“She only said that dad would wake up with nightmares from the war a couple times a week,” said the middle son, Frank.

“It was an unspoken pact,” Richard explained. “Men who came back needed the support of their significant others. Sometimes that relationship worked — like my parents — and sometimes it didn’t.

“But the ‘Greatest Generation,’ as a whole, do not talk about it.”

Tom Brokaw, the journalist/author who championed the term “Greatest Generation,” reached out to DeVita and asked to interview him for the 70th anniversary of D-Day.

The retired pattern maker agreed. He talked to Brokaw, and many other news outlets and civic groups, including the Washington, D.C.-based American Veterans Center.

“When our mother died, that sort of gave him permission to start telling the story,” Frank said.

But DeVita was clear throughout: He wasn’t promoting his own heroism. He wanted the world to remember the sacrifices of the fallen.

“I’m not a hero,” DeVita concluded in the 2022 interview. “I’m a survivor. There’s a cemetery in France, up in Normandy — 9,400 kids in the ground. Those are my heroes.”

Frank DeVita passed away in 2022 at age 96.