By Joann Stevens

WASHINGTON (OSV News) — Raising public awareness about the role of slavery in building the U.S. Catholic Church and sparking hopes for racial justice and reconciliation were themes that emerged in a recent discussion at The Catholic University of America in Washington.

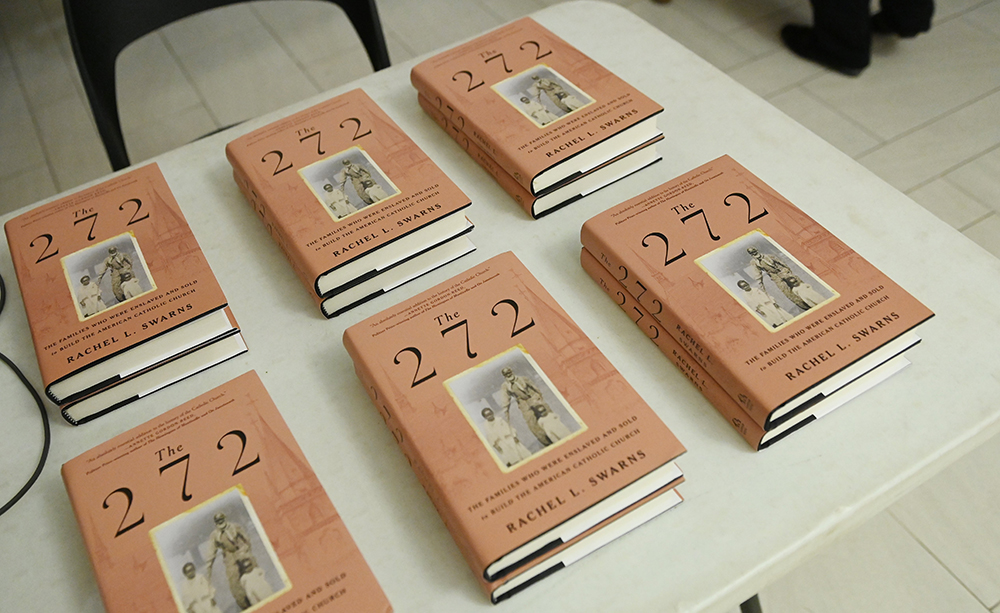

The discussion featured former New York Times journalist Rachel L. Swarns, author of the bestseller “The 272 – The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church,” and Laura E. Masur, an assistant professor in the department of anthropology at The Catholic University of America.

The Feb. 1 forum at Catholic University’s Heritage Hall drew a diverse audience of more than 200 participants, including high school and college students; department heads and faculty members; clergy; and Washington-area residents and Maryland and Louisiana descendants of the 272 enslaved men, women and children who were sold in 1838 by the Maryland Jesuits to Louisiana plantation owners.

That sale helped ensure the financial survival of Georgetown College, which later became Georgetown University.

In welcome and introductory remarks, Thomas W. Smith, dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Catholic University, told of being “stopped cold in my tracks” after reading Swarns’ article in The New York Times.

“I was never told this history,” said Smith, a graduate of Georgetown University. Learning it has provoked deep reflection about his alma mater and the church that “I thought I knew and that I love,” he added.

Praising Swarns’ work, he said, “It is deeply humanizing scholarship and history about people who were hidden away and have now been brought into the light.”

Masur, who facilitated the discussion, has led archaeological field work at Sacred Heart cemetery in Bowie, Maryland, that has unearthed what are believed to be hundreds of unmarked graves of enslaved people who worked at area Jesuit plantations during colonial times and before emancipation.

She asked Swarns about her research methods, the Mahoney family members who are the focus of the book, and decisions made by Jesuit priests then including Father Joseph Carbery, a mid-level plantation manager who was a willing but ineffective advocate to stop the sale, and the ambitious, Virginia-born Father Thomas Mulledy, who became Georgetown’s president and was the chief architect behind the university’s evolution, the sale of the 272, and the Jesuits’ rise to power in the United States, by any means necessary.

The conversation unfolded like a suspense story, with Swarns speaking in a quiet, calm voice, as she gave names and humanity to enslaved people who are more often reduced to being described as property without names or human feelings.

“I am a journalist,” Swarns reminded the audience. “I don’t do commentary. I am not a policy- maker. I am a storyteller.”

“The 272” is a family and an institutional story. It begins with the arrival of a teenaged Ann Joice, a Black immigrant from England to Maryland around 1676. Lured by promises of freedom, opportunity and escape from religious persecution, Ann contracts herself to the powerful Calvert family as an indentured servant. She naively trusts the process until a Calvert cousin she is sent to work for destroys her contract papers, forcing her into permanent enslavement.

Her freedom is stolen, but not her voice. Ann spends the rest of her life resisting, telling her descendants, who include the Mahoney family, “our freedom was stolen from us,” and encouraging them never to forget, and asking them to pass their story down.

And they do, through:

— Court battles that eventually give Swarns access to official court depositions and witness statements.

— Violent resistance that some paid for with their lives in events that captured news headlines.

— And their Catholic faith witness. Swarns said Jesuit baptism and confirmation records show a long commitment to Catholicism that even led some family members into religious life “to build a church more responsive to Black Catholics.”

Raised Catholic and still practicing the faith, Swarns said, “I felt inspired and still do by these families.”

As British soldiers advanced on the Maryland plantations during the War of 1812, the priests fled, leaving the enslaved to fend for themselves.

Harry Mahoney protected the Jesuit’s wealth, hiding thousands of dollars, valuable church artifacts, and even the enslaved girls. When the priests returned to what they thought was certain ruin, Harry restored their wealth. The priests promised to never forget “his valor and loyalty,” and that Harry would never be sold, Swarns wrote. The promise was ignored under Father Mulledy’s leadership.

Swarns told the audience she didn’t know whether Father Carbery, who had come to respect the faith, integrity and skills of the Mahoney family members, was “unimaginative” in his advocacy for them or just powerless. As sale of the 272 approached, he enjoined them to “pray” it would not take place. When that failed, he pleaded with superiors to save them. When that failed, he told the Mahoneys, “Run!”

Two sisters, Anna and Louisa Mahoney, took divergent paths. Louisa and her mother ran and hid in the woods and Louisa was later purchased by Father Carbery. Anna was sold into the Deep South.

Following the 90-minute discussion, an engaging question-and-answer session ran for another 30 minutes.

A man who identified himself as Salvadoran asked why it took Catholics in the United States so long to acknowledge and discuss church history long recognized and discussed in Latin America. Swarns replied that sometimes the American history was unknown; sometimes it was conveniently forgotten.

High school students from Gonzaga College High School and Holy Trinity Parish in Washington asked about the scope of her research. Swarns explained that it is not just about Georgetown University or the South, but the American Catholic Church and institutions supported by slavery. For example, the New York Life Insurance Company insured enslaved people as property. Jesuit institutions in New England and elsewhere received support from the wealth of the Maryland plantations.

One woman asked how Swarns protects herself from the trauma of her research and the hard truths she uncovers.

Many older journalists have learned to repress traumas experienced as journalists, Swarns said, adding that younger journalists tend to discuss them.

“I have a running conversation with my son about the moment when Carbery warns the Mahoneys to run,” she said. “One sister makes it. The other doesn’t. If you have five minutes to run, who do you take? Can you even run?”

“I’m still figuring out how to wrestle with the history and its impact on me. I tell myself that I can’t afford to look away, and I won’t. I just keep going,” Swarns said.

After her talk, in an interview with the Catholic Standard, the Washington archdiocesan news outlet, Swarns said, “We have to wrestle with this (history) as a country. It’s urgent that we do so now,” adding that the history and lessons learned about the 272 are as central to current events as the story is to its place in American history.

Catholic high schools and institutions such as Harvard, Loyola and Catholic University are examining their histories with slavery. The Jesuits have apologized for their betrayal of the 272 families and pledged to raise $100 million for restorative justice programs. Georgetown University has established The Descendants Truth & Reconciliation Foundation to support racial healing efforts and educational advancement for descendants of the 272 families.

The history of Catholic priests as enslavers “is bittersweet,” said Henrietta Pike, the great-great granddaughter of Louisa Mahoney. “But I have been a devout Catholic for years. This is my faith. God did not do this (enslavement) to them.”