By Cindy Wooden

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — In many places in the world, including in Rome, people with disabilities cannot enter Catholic churches because of the architectural barriers, but even when they do, “we are not asked anything and we are not asked to participate either,” said Enrique Alarcón García.

That changed with the preparations for the Synod on Synodality, said Alarcón, who is president of Frater España, a Christian fraternity of people with disabilities in Spain.

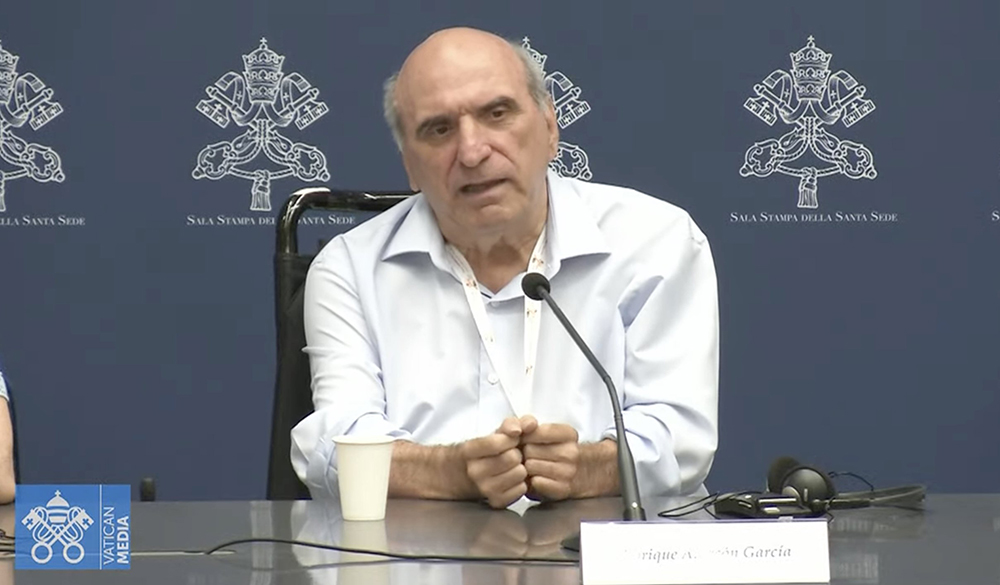

Alarcón, a papally appointed member of the assembly of the Synod of Bishops, spoke to reporters Oct. 14 about his synod experience.

While many people hear about the synod’s focus on “inclusion” and think of the synod’s controversial discussions about LGBTQ Catholics or more roles for women, Alarcón said those weren’t the first topics his community thought of. “The church came out with a bright sign with the word ‘inclusion’ on it, a house for all. Inclusion, we said, but is it possible?”

The Dicastery for Laity, the Family and Life had organized synod listening sessions for people with disabilities in 2022, which Alarcón said was a “great surprise,” one that continued when he and four others were asked to submit a report to the synod and, even more, when he was named a synod member.

Still, he had some suspicions that his presence was “something good for publicity” and that, seated in his wheelchair, he would be the object of pity or paternalism from the cardinals and bishops, something he said he has experienced in the past.

“But the pope has spoken to us through this whole synodal process and tells us, ‘No, as a baptized member of church, you are a member by right and you also are called to be an evangelizing member,” he said. “That brought real joy to my heart and is making it possible for people with disabilities around the world to start looking at the church differently.”

For Alarcón, the Vatican’s decision not to hold the assembly in the theater-like audience hall with its steep rows of chairs, but rather in the audience hall at round tables, was more than a change of atmosphere.

With his wheelchair, he could sit at a table with other members, “occupying the same place and at the same height,” he said. It was a sign of solidarity and of a sincere desire to work toward being “a church where we can all be together and where we are all called to carry out our evangelizing task,” he said.

The assembly’s work in small groups, where members take turns listening to each other, “is very important,” he said, “because for a person with disabilities, in most of the world, it is very difficult to be able to speak with people who are educated not to listen, but only to speak, as happens often with bishops and, especially, cardinals.”

“I think the synod has a pedagogical character, because the hierarchy is seeing that it is possible to have a dialogue, to listen,” Alarcón said.