By Cindy Wooden

ROME (CNS) — Catholic and Jewish institutions announced Sept. 7 the discovery of a previously unpublished list of several thousand people, mostly Jews, who were hidden in Catholic convents and monasteries in Rome during the Nazi occupation of the city.

The documentation regarding 4,300 people — including 3,600 of whom are named — given refuge by women’s and men’s religious congregations was found in the archives of the Jesuit-run Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome, also known as the Biblicum. The registry was compiled by Jesuit Father Gozzolino Birolo, bursar of the Biblicum, between June 1944 and the spring of 1945, immediately after the liberation of Rome by the Allies, according to a press release.

Scholars from the Biblicum, the Pontifical Gregorian University, the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, the Historical Archive of the Jewish Community of Rome and the Department of Cultural Heritage and Cultural Activities of the Jewish Community of Rome discussed the documentation at a closed-door meeting Sept. 7 at the city’s Shoah Museum.

“The list of 100 women’s and 55 men’s religious congregations that offered hospitality, together with the numbers of the persons who were accommodated by them, had already been published by the historian Renzo De Felice in 1961,” the press release said, “but the complete documentation had been considered lost.”

The press release said having the names of 3,600 people sheltered allowed a comparison with documents kept in the archives of the Jewish Community of Rome and indicated that at least 3,200 of the people listed were Jewish. However, Silvia Haia Antonucci, archivist at the Historical Archive of the Jewish Community of Rome, told Catholic News Service Sept. 7 that the comparison has not been completed and it is still unclear how many names on the list were members of the Jewish community.

Until the full comparison is complete, she said, it would be impossible to say how many of those hidden survived the war.

The documentation explains “where they were hidden and, in certain circumstances, where they lived before the persecution,” details which “significantly increases the information on the history of the rescue of Jews in the context of the Catholic institutions of Rome,” the press release said.

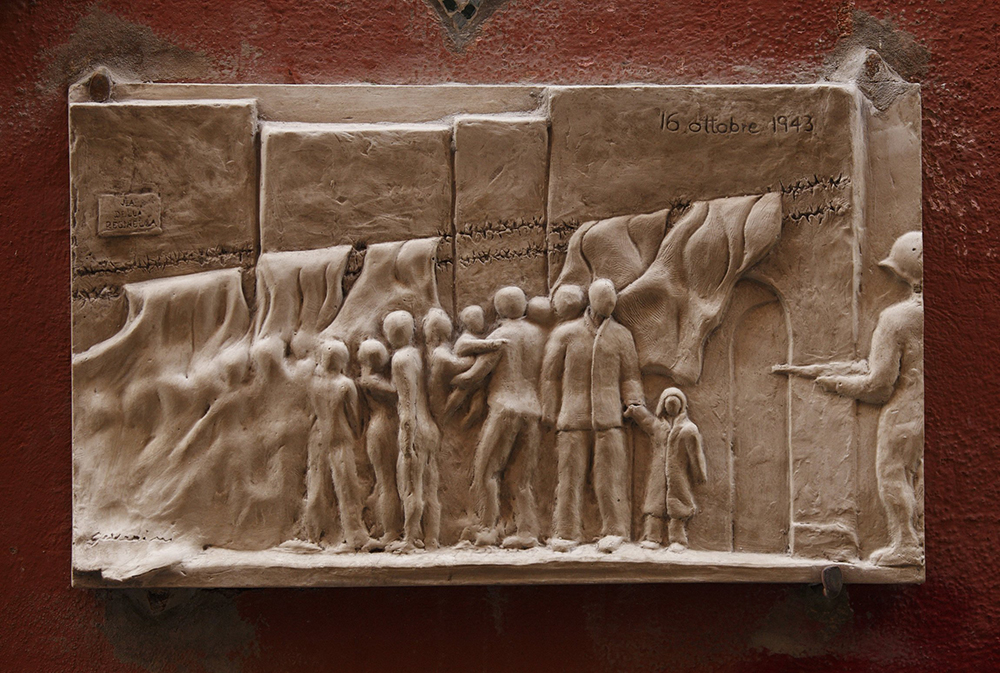

Rome was occupied by the Nazis for nine months, starting from Sept. 10, 1943, until the Allied forces liberated the city June 4, 1944.

“During that time,” the press release noted, “the persecution of the Jews led, among other things, to the deportation and murder of nearly 2,000 people, including hundreds of children and adolescents, out of a community of approximately 10,000 to 15,000 Jews in Rome.”

Pope Pius XII, who was pope during World War II, has been criticized for not publicly condemning the Nazi regime, its genocide of Europe’s Jews and the roundup of Jews in Rome.

Catholic officials and a variety of historians have argued that Pope Pius facilitated hiding thousands of Jews on church property and coordinated efforts to rescue and locate displaced persons in Europe during and after the war.

Antonucci told CNS, “That Jews were saved in convents is not news. The question of whether it was with the personal encouragement of Pope Pius is another question, one that continues to be studied.”

Various lists of Jews hidden from the Nazis in Rome convents and monasteries already exist, she said, “but this is the first list that compiles them all” and provides more than just vague details about the individuals and about where they were hidden.