by Elise Ann Allen, Special to The Tablet

ROME — When Pope Francis visited Mongolia Aug. 31-Sept. 4, representing one of the Church’s smallest and most remote communities, it showcased his repeated love of the peripheries and served as an opportunity to introduce the Catholic Church and its works to a place still largely unfamiliar with Christianity.

Prior to the pope’s departure, Cardinal Giorgio Marengo, apostolic prefect of Ulaanbaatar, who at 49 is the church’s youngest cardinal and who got his red hat from Pope Francis just last year, said in a video series for Fides News that the visit was a concrete illustration of the pope and his pastoral priorities.

“We know how much the Holy Father has the dimension of the periphery in his heart, understood as an experience, perhaps, of marginality, even of minority, of a life of faith that is confronted with a majority that has other points of reference,” Cardinal Marengo said.

Pope Francis traveled to the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar, making him the first pope to visit the country, despite a lengthy history of relations dating back to the 13th century.

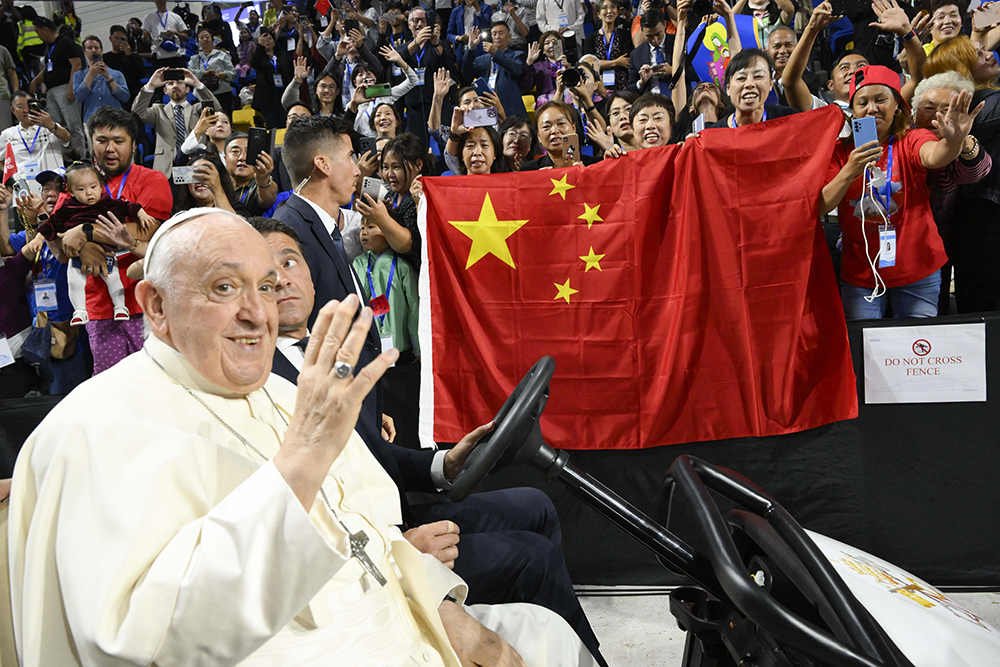

Bordered by both Russia and China, Mongolia is of great geopolitical interest as the Vatican seeks to strengthen ties with Chinese authorities and to engage Russian leaders in peace talks amid its ongoing war with Ukraine.

The Vatican has long been engaged in a courtship of sorts with both countries, so the pope’s visit to Mongolia, some 800 years in the making, was considered a significant step in drawing closer to these two geopolitical giants.

However, apart from the geopolitics involved, there was a clear pastoral motive for the visit to Mongolia, where Catholics number less than 1,500 in a population of roughly 3.4 million, most of whom are Buddhist.

Catholicism has had a presence in Mongolia for centuries, yet it essentially disappeared during the communist era in the 1900s, with religious freedom returning only in 1992 after Mongolia’s break from communism and the drafting of its own constitution.

Various religions slowly began to regain their foothold in the area, with Catholic missionaries themselves arriving the same year communism fell.

Currently Mongolia is around 53% Buddhist, with the majority adhering primarily to Tibetan Buddhism. Shamanism, Islam, Hinduism, Protestantism, and Judaism also have a presence, in addition to Christianity.

Leaders from each of these traditions were present at an ecumenical and interfaith meeting with Pope Francis on Sunday, Sept. 3, during which the pope highlighted the important contribution religions make to society through their works and promotion of the concepts of solidarity and global fraternity.

Yet while Catholicism is slowly growing and missionaries on the ground reported that many people, especially those from other branches of Christianity, are becoming Catholic, the Church itself and its teachings are relatively unknown.

Throughout the trip, Pope Francis used his speeches to essentially introduce the essential beliefs of the Catholic faith and to outline why it is beneficial to society, given its various charitable and social works, especially those aimed at caring for the poor and the environment.

In a speech to missionaries and bishops Saturday, Sept. 3, the pope said their task is to spread “the joy of the Gospel,” and that “Jesus is the good news, meant for all peoples, the message that the Church must constantly proclaim, embody in her life and ‘whisper’ to the heart of every individual and all cultures.”

He repeatedly outlined the Church’s various social initiatives in Mongolia in his speeches, which include agricultural programs aimed at introducing greenhouses in private homes to curb poverty and malnutrition, educational programs, and support programs for women and children facing domestic violence.

The Church also assists migrants and allocates funds from foreign aid to various local initiatives, with most beneficiaries being non-Catholic, while also promoting both anti-discrimination and anti-corruption efforts.

Caritas International, the Church’s global charitable organization, has been present in Mongolia since 2000, assisting herders in harsh weather, providing aid to the poor, and promoting a just and sustainable development.

Through seven different programs, Caritas Mongolia assists in programs dealing with education, social and humanitarian aid, food security and agriculture, migration, rebuilding livelihoods for those struggling, and community-building projects in rural areas, as well as reducing the fallout from natural disasters.

While in Mongolia, Pope Francis pointed to these initiatives as a reassurance to state leaders in the country, but which was equally directed to Chinese authorities, that they have nothing to fear from the Church.

Jesus, he told missionaries and bishops, did not send his disciples “to spread political theories, but to bear witness by their lives to the newness of his relationship with his Father … which is the source of concrete fraternity with every individual and people.

“The Church born of that mandate is a poor Church, sustained only by genuine faith and by the unarmed and disarming power of the risen Lord, and capable of alleviating the sufferings of wounded humanity,” he said.

For this reason, Pope Francis insisted that “governments and secular institutions have nothing to fear from the Church’s work of evangelization, for it has no political agenda to advance, but is sustained by the quiet power of God’s grace and a message of mercy and truth, which is meant to promote the good of all.”

Pope Francis during the brief trip also sought to regularize the status of foreign missionaries, who despite the relatively good relationship between Church and state have faced difficulties with visa applications.

Oftentimes missionaries, no matter how long they’ve lived in Mongolia or how well they speak the language, receive only short-term visas, meaning they are forced to travel abroad every three months without having the certainty of whether they will be allowed back in.

The Mongolian government also requests that for every missionary visa granted, Catholic entities pay certain fees and employ a number of local citizens.

During his visit, Pope Francis in several speeches, to national authorities and to missionaries themselves, mentioned that a bilateral agreement between Mongolia and the Holy See is currently being negotiated that would regularize missionaries’ immigration status.

He also sought to clarify the motive for the church’s charitable efforts, using the inauguration of the new House of Mercy charitable center in Ulaanbaatar Monday, Sept. 4 to explain the Catholic concept of charity, insisting that it was not a money-making business nor an endeavor aimed at obtaining conversions.

Rather, charitable service is undertaken “to alleviate the suffering of the needy, because in the person of the poor they acknowledge Jesus, the son of God, and, in him, the dignity of each person, called to be a son or daughter of God,” he said.

The pope also made a plug for peace that was likely not lost on Russia, which sits along Mongolia’s northern border, asking in his opening speech to national authorities that God would “grant that today, on this earth devastated by countless conflicts, there be a renewal, respectful of international laws, of the conditions of what was once the ‘Pax Mongolica,’ that is, the absence of conflicts.”

The pope added, “May the dark clouds of war be dispelled, swept away by the firm desire for a universal fraternity wherein tensions are resolved through encounter and dialogue, and the fundamental rights of all people are guaranteed!”

Lay Catholics and missionaries who participated in papal events throughout Pope Francis’ visit routinely expressed joy at the pontiff’s presence, saying repeatedly that they were “shocked” when the visit was announced, and surprised that he would visit such a small flock.

Pope Francis has long prioritized the world’s peripheries in both the cardinals he has named and in his international travel, skipping over major world capitals and preferring to visit places with small Catholic minorities, such as Georgia and Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

In his remarks during the video series, Cardinal Marengo said Mongolia “represents an experience of being Catholic in a condition of minority, at times of marginality” compared to other areas of the world.

In this sense, the church in Mongolia, he said, can potentially offer the rest of global Catholicism “the gift of the freshness of a faith that questions itself, that allows itself to be questioned by reality, that doesn’t have great external forces or signs to rely on, but counts on the living presence of the risen Lord and on dialogue, on caring for the little ones.”