WASHINGTON — When people say they went through a “dark night of the soul,” it’s pretty much a given that they’re talking about a very rough time or an intense spiritual crisis.

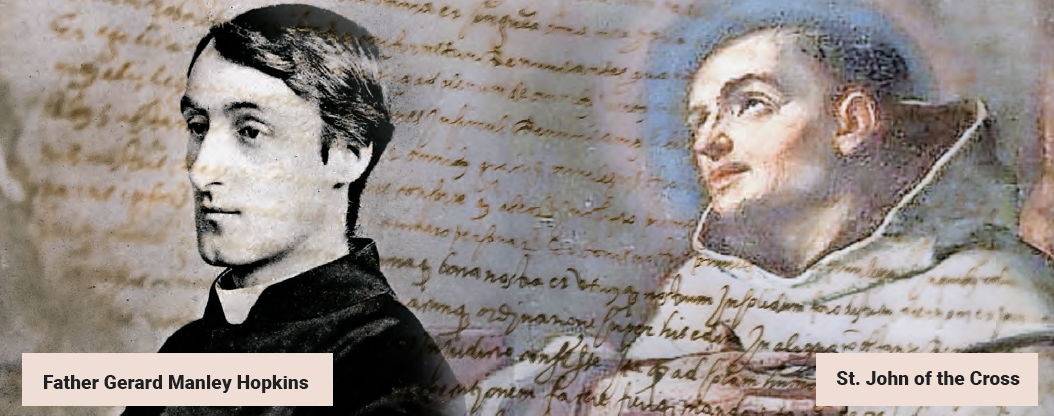

But this phrase, which is the title of a poem written in the late 1570s by the Carmelite priest and Spanish mystic St. John of the Cross, is not really about the gloom and despair that people often associate with it, according to a professor at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut.

June-Ann Greeley, an associate professor in the university’s Catholic Studies Department, said the poem’s essence is about coming before God with absolutely nothing and finding ultimate fulfillment there.

With World Poetry Day falling on March 21, Greeley and other experts spoke to The Tablet about famous poets who were priests and how their works reflected their Catholic faith.

When people think of St. John of the Cross, even if they’ve heard of “The Dark Night of the Soul,” they might not know he was a priest who co-founded the Discalced Carmelites.

And Greeley points out that the dark imagery he uses is “not the void,” as many imagine, but instead a way to describe coming before God without anything, even aids, such as light, and then to be completely “present with the love of God” and “allowing the presence of God to take over everything.”

The eight stanzas of this poem include the line “O, happy lot,” twice and also the phrase “In that happy night,” hardly depicting that all is lost. But that is not to say that St. John of the Cross got to that point without struggle. He wrote this work after being persecuted and imprisoned in a tiny cell for nine months. He was put there by his fellow Carmelites for his attempts to reform the order.

Greeley said the poet’s ability to come out of that traumatic experience and write free of anger and resentment is akin to the writings found in small pieces of paper in Nazi concentration camps, revealing that in “the darkest of all places, there were incredible points of light in the soul.”

Greeley, who has taught an annual seminar that looks at both St. John of the Cross and his contemporary, St. Teresa of Ávila, said the poet’s most well-known work requires readers to rethink that light is good and darkness is bad.

“That’s a very exciting moment, being open to that possibility of a different way of thinking of our humanity,” she said.

She also said students initially have a hard time with some of his works, as would modern readers, because he is a mystical poet using a language style many are not familiar with.

Her advice is to read his poems, including “Spiritual Canticle,” which express the poet’s burning love for God, with someone else or even in a reading group, and then to talk about it.

She said these writings from centuries ago “offer a remedy for sterile Catholicism” or a dullness in any faith where there is not that “passion of love for God.”

This unabashed love for God that St. John of the Cross wrote about, she said, “makes us ask questions about our own faith life,” such as: “Would we even know if we are in the presence of God? Have we lost our capacity to have this?”

Another renowned priest-poet was the Jesuit priest from England, Father Gerard Manley Hopkins. Hopkins, a Victorian-era poet who also wrote of his deep love for God, expressed this primarily in descriptions of nature.

Father Hopkins, a convert to Catholicism, burned all of his poems when he became a priest and didn’t take up writing again for several years. He died in 1889 when he was 44 from typhoid fever, and his works were not published until 30 years after his death.

Catharine Randall, a scholar in residence at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, and author of the 2020 book, “A Heart Lost in Wonder: The Life and Faith of Gerard Manley Hopkins,” said these two Catholic poets had very different styles of living and writing, but there are common threads.

St. John of the Cross was very much contemplative, she said, whereas Father Hopkins was not. “He was very much in the world,” aware of its “rawness and the fatigue of tired landscapes” but also the beauty of nature.

The closest he came to echoing themes of St. John of the Cross, she said, was in his sonnets that turn inward or his poem “Felix Randal,” which tries to understand what is going on in his soul.

When she tells people she wrote a book about him, they often start reciting “The Windhover,” his poem about a hawk. What they don’t realize, she said, is how the poem is rich in Christian symbolism, starting with the hawk itself.

Randall said Father Hopkins’ poetry “doesn’t tell you what to think but shows you what he loves,” and his sonnets portray “a real wrestling with God that goes on … of loving God and not knowing how to be with him.”

Daniel Rober, who, like Greeley, is also an associate professor at Sacred Heart University in the school’s Catholic Studies Department, said Father Hopkins is “a really interesting poet for the Church today, especially the Church of Pope Francis” because of the way he writes about God and the natural world.

He said Father Hopkins’ writings are hard for some students to jump into because they are written in a different format and suggested, as did Greeley with St. John of the Cross, that these poems are better understood when read aloud and when groups try to figure out their meaning.

These poems still speak to us today, he said, about faith and the uniqueness of each person and all aspects of the natural world.

Or as Father Hopkins, in his poem, “Pied Beauty,” put it: “Glory be to God for dappled things.”