This year, as the nation observes Juneteenth, many Brooklynites are surprised to learn their city’s harsh history of slavery

FLATLANDS — Growing up in an African-American family, Dr. Steven Craig Wilder was taught that his hometown, Brooklyn, had been a bastion of famous abolitionists.

Based on what he learned in school, Wilder assumed slavery was largely a Southern institution, the opposite of what was believed about Northern states, including New York.

“But all the elements of that story are false,” Wilder says. The truth is that New York had the harshest slave code anywhere north of South Carolina, allowing slave owners to brand, castrate, and mutilate people they owned as property.

“And Brooklyn,” he said, “was one of the strongholds of the slave economy in the 18th century.”

New Amsterdam to Breuckelen

Wilder is from Bedford-Stuyvesant, where he and his family belonged to Holy Rosary Parish. He is now an author and lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Wilder said the truth about slavery in Brooklyn gradually opened to him during his research for his undergraduate degree from Fordham University. His doctorate is from Columbia University, where he wrote a dissertation titled, “Race and the History of Brooklyn, N.Y.” He also wrote “A Covenant with Color: Race and Social Power in Brooklyn.”

With these credentials, he served on the advisory board of “Brooklyn Abolitionists/In Pursuit of Freedom” — a public history exhibit displayed from 2014 to 2019 at the Brooklyn Historical Society, now called the Center for Brooklyn History.

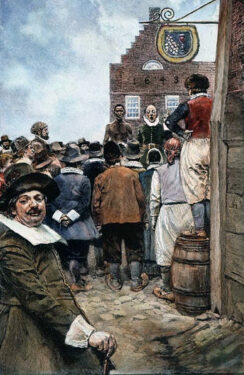

Wilder described how the Dutch in the early 1600s brought slavery to their colony at the lower tip of Manhattan. They expanded to “Breuckelen” on Long Island — present-day Brooklyn — where they built vast farms that depended on the labor of enslaved people.

This agricultural juggernaut of corn, wheat, cabbage, and other crops fed “New Amsterdam,” the Southern colonies, and the West Indies.

That continued when the English took control of New Amsterdam, and later when Americans won their independence from the crown.

Dr. Prithi Kanakamedala, a history professor at Bronx Community College (CUNY), was the lead historian for “Brooklyn Abolitionists/In Pursuit of Freedom.” She said that by the end of the American Revolution in 1783, slavery was on the decline in urbanized Manhattan.

“But,” she said, “Brooklyn tells a very different story.”

By 1800, 6,000 people lived there, but about one-third of them were slaves.

‘Too Dreadful to Behold’

Descriptions of slavery begin the autobiography, “The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea.” The author, born in 1773, was kidnapped as a toddler with his family in the port city of Calabar, along the southern coast of Nigeria.

A slave ship carried them to New York City where a Dutch farmer purchased them to work his fields in what today is the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. Jea later won his freedom and became a seaman and a preacher. But his life as a slave was spent toiling in the fields for 20 hours, fed only by a corn-based gruel and dark bread, plus an occasional scrap of meat with potatoes.

“The horses usually rested about five hours in the day while we were at work,” Jea wrote. “Thus did the beasts enjoy greater privileges than we did. We dared not murmur, “for if we did, we were corrected with a weapon an inch-and-a-half thick, and that without mercy.”

Jea also described slaves being flogged, “in a manner too dreadful to behold.”

“Often,” he wrote, “they treated the slaves in such a manner as caused their death, shooting them with a gun, or beating their brains out with some weapon, in order to appease their wrath.”

A Myth Emerges

Jea wrote his autobiography during the early 1800s in England. It went largely unnoticed until scholars rediscovered it in 1983. Had it become more widely known earlier, there might have been a different understanding of slavery in Brooklyn.

“So much of what we do as historians is to dig in the archives for evidence,” Kanakamedala said. “But we don’t often get a lot for Brooklyn like John Jea’s narrative.”

Consequently, she said, a myth emerged “that slavery in the South is bad, but slavery in the North is relatively mild. But here is John Jea, in his own words, telling you that actually it was traumatizing, it was horrific, and it was sinful.”

Wilder noted that early biographers of Brooklyn’s pioneers describe their slaves with happy nostalgia. For example, Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt (1824-1902), a prominent chronicler of Long Island history, wrote that the Flatbush home of her childhood had matronly enslaved women with magnetic personalities that endeared them to the center of family activity.

“It is not probable,” she wrote, “that slavery ever exhibited its worst features on Long Island. A kindly feeling existed between the owner and the slave.” Vanderbilt also gave generously to causes that improved the lives of emancipated slaves. But Wilder said her writings were incomplete.

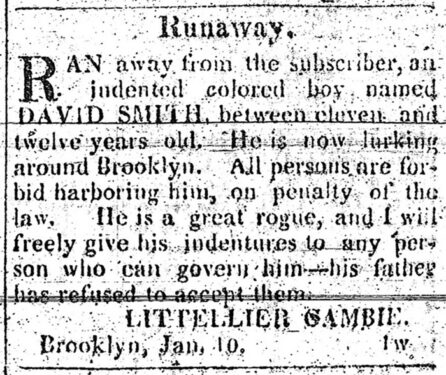

“The purpose of that, of course, is to populate the myth of gentle slavery,” Wilder said. “But we know those very same families were continually advertising in newspapers for the capture and return of enslaved people who ran away from their property.

“None of those people ever get interviewed. They never get a chance to respond about what the nature of slavery was.”

Gradual Emancipation

The website for “Brooklyn Abolitionists/In Pursuit of Freedom” is still up and full of content. It describes a period of “gradual emancipation” starting immediately after the Revolution.

During this time, the nation’s new independence inspired the rise of anti-slavery movements. Subsequently, New York State laws started to allow the emancipation of slaves based on a complicated age-based formula. For example, a 1799 law declared that enslaved children born after July 4 of that year would be free at the age of 28, if male, and 25, if female.

But slavery continued for everyone born before 1799 until New York finally outlawed the institution in 1827, one of the last Northern states to do so.

Others were freed through “manumission” — a practice going back to the days of ancient Greece and Rome in which a property owner grants the freedom of a slave.

It is believed that Jea, having embraced Christianity, appealed to an owner’s religious sensitivities to release him, Kanakamedala said.

As early as 1808, communities of free black citizens created their own neighborhoods in Brooklyn, such as the Dumbo-Vinegar Hill area, and Weeksville, now part of present-day Crown Heights. In these communities, they built businesses, schools, and churches.

Still, freed blacks on Long Island lived under a residual terror of being identified as escaped Southern slaves. The federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed “commissioners” to catch suspected escapees and return them to their owners.

One man, James Hamlet of Williamsburg, was nabbed by slave catchers who claimed he fled bondage in Maryland. He was taken to Baltimore and put on sale. But outraged black abolitionists in Brooklyn took up a collection, paid the purchase price, and returned him to his family.

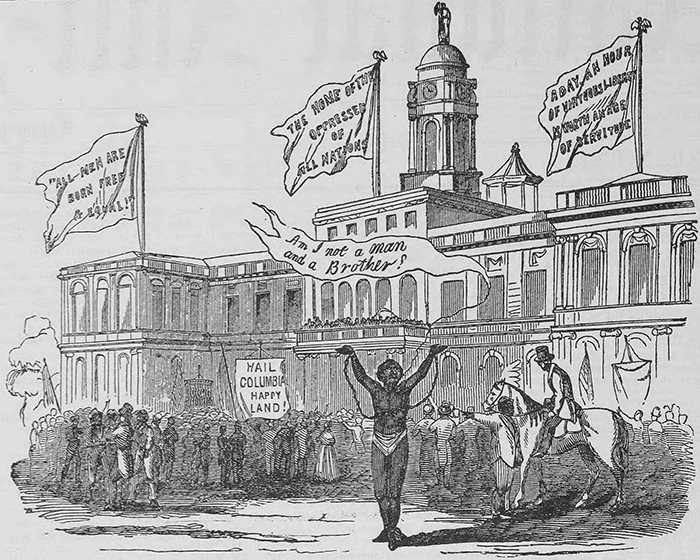

“And so,” Kanakamedala said, “what we see in 1850 are huge, powerful sermons being given in the churches about, ‘Yes, the Fugitive Slave Act is legal. But is it moral? Is it ethical?’”

Brooklyn’s abolitionist movement had arrived, according to Kanakamedala.

“It truly becomes multiracial. It is black and white Brooklynites coming together to say, ‘Slavery needs to end in the United States.’ ” Kanakamedala said. “Yes, white abolitionists were at the center of that movement, and they were incredibly important abolitionists. But where would the seeds of the abolitionist movement come from?

“Well, it was with that free black community.”