Boxing isn’t exactly a sport that exemplifies Catholic values. Two competitors enter the ring with one goal in mind: to knock out their opponent.

However, just because the sport by nature is violent, that hasn’t stopped a few boxers from openly professing their faith.

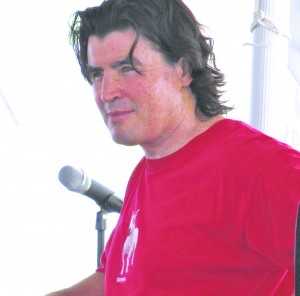

Born in England and raised in Ireland, Seamus McDonagh, 59, always had a strong Catholic faith. His father was a fighter in England, which led to McDonagh taking up boxing.

“I didn’t really like boxing, but I was good at it since my dad made me train,” he said.

At age 19, McDonagh and his sister escaped the struggling Irish economy and moved to Bay Ridge, where they became parishioners at Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Sunset Park, and later St. Patrick’s, Bay Ridge. It took some time though for the young boxer to adjust.

“It was culture shock totally,” he said. “I hated it when I came here at first.”

Upon arriving, McDonagh began boxing locally as an amateur. After split decisions in 1983 and 1984, he won the 1985 New York Golden Gloves Heavyweight Championship, which put his career on the map. Unfortunately, he dealt with the demons of alcohol abuse and depression along his journey.

But through it all, McDonagh — who blessed himself before every fight — relied on the power of God to help him overcome his addiction.

“Everybody has problems, so I need some way to deal with my problems,” he said. “Like (Albert) Einstein said, ‘No problem can be solved at the same level of consciousness that created it.’ So you must seek a higher power.”

McDonagh said once he gained the consciousness that there was a higher power and he wasn’t alone in his recovery, things started to turn around.

“There is this power, so I just need to avail off that power somehow,” he said. “I avail off that power, and then I’m given the power to deal with my problems.

“Everybody is a child of God. It’s a tough world, and the more sensitive you are, the harder it is to live in the world. Someone like me needed more power.”

With this new confidence, McDonagh was prepared for a professional boxing career. Ironically, he says the true reason he turned pro was to pay for his second semester of college at St. John’s University, Staten Island campus, where he studied English literature.

“Things in my life just changed drastically,” he said. “I went from being a suicidal alcoholic to having hope in life.”

For most of his career, McDonagh fought as a cruiserweight, the weight class between light-heavyweight and heavyweight. He won the first nine matches of his career — seven by knockout.

In May, 1989 in Atlantic City, N.J., McDonagh fought a heavyweight match against Cecil Coffee, who had knocked out 90 percent of his opponents and had never been knocked down himself in his 23 pro fights. Despite being the underdog, McDonagh landed his patented left hook in the sixth round, which knocked out Coffee and gave McDonagh the victory.

Before the fight, he was already ranked the No. 3 cruiserweight in the world, but defeating Coffee earned him the No. 9 world ranking among heavyweights. Just a few months later, McDonagh would be in store for the biggest fight of his life.

In early 1990, the boxing world salivated over the possibility of seeing undefeated heavyweight champion Mike Tyson fight up-and-coming star Evander Holyfield. Tyson fought Buster Douglas in February of that year in Toyko, Japan, in what was supposed to be merely a tune-up fight for “Iron Mike.”

However, Douglas knocked out Tyson, which eliminated any chance of a Tyson-Holyfield bout. As a result, McDonagh was given the offer to fight Holyfield on June 1, 1990.

“Psychologically I wasn’t prepared, but physically I was in great shape,” he said.

McDonagh came out swinging, but his efforts stood little chance against the powerful punches of Holyfield. After already being knocked down twice, McDonagh fell a third time after Holyfield connected with a left hook 44 seconds into the fourth round. At that point, the referees stopped the fight for safety reasons.

Soon after the loss to Holyfield, McDonagh retired with 19-3-1 career record. He continues to pray and meditates twice daily as a way to remain in communication with God.

Fighting Evolves into Acting

Sitting at his computer in 2007, McDonagh opened an e-mail message from Bobby Cassidy Jr., a writer for Newsday who used to cover McDonagh’s boxing career. Cassidy asked McDonagh to star in a play he had written about the life of his father, Bobby Cassidy Sr., the No. 1 ranked light-heavyweight in 1975 who overcame an alcohol addiction.

McDonagh loved the script and agreed to portray the elder Bobby Cassidy Sr. in the play, titled “Kid Shamrock.” The Off-Broadway production ran in June, 2007; February, 2011; 10 nights in late November-early December, 2011 at TADA! Theater in Manhattan; and most recently at Plattduetsche in Franklin Square, L.I., on Aug. 11 of this summer.

Cassidy Sr., a Levittown, L.I., native and the play’s narrator, was raised Catholic in St. Bernard’s church, Levittown, and St. Bridget’s church, Westbury, L.I. He recorded 59 career wins, 27 via knockout. However, like McDonagh, his alcohol addiction plagued his life for a time.

“I got down on my hands and knees, and I asked God to stop me from drinking,” Cassidy Sr. said. “Being a Catholic, knowing that God is the power almighty…if anything could do it, Jesus Christ can. And he did it.”

It’s been 38 years since Cassidy Sr.’s last drink. He learned discipline through his faith, which his son details in the play. Cassidy Jr. actually includes in the play spoken lines that his father said to him as a child.

Other than Cassidy Sr. and McDonagh, former boxers John Duddy and Mark Breland act in the play, and former heavyweight champion Michael Bentt served as the director.

“It’s not about culture or race or religion; it’s about the essence of who you are,” said Bentt, a Cambria Heights native and four-time New York Golden Gloves champion. “The story is transcendent. It’s about people.”

Though no future performances are currently scheduled, the cast and crew are hoping “Kid Shamrock” expands. Bentt said they’re trying to find interest in taking the play to Los Angeles and even overseas to Ireland.

“I hope someone picks it up,” McDonagh said. “It’s a beautiful play, and it parallels my story.”

Click here to see Currents News Director Ed Wilkinson’s interview with Seamus McDonagh.