By Christopher White, National Correspondent

NEW YORK – In recent years, the tug-of-war between the archdiocese of New York and the diocese of Peoria over the body of Fulton Sheen provided American Catholics a glimpse into the extreme lengths church leaders would go in order to influence the process of canonization.

News that the Vatican was halting Sheen’s planned beatification – originally scheduled to take place last month – while his record on sex abuse cases is further scrutinized is further proof of how complex the canonization process is, and how ultimately, the buck stops with Rome.

In her new book, “A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American,” University of Notre Dame historian Kathleen Sprows Cummings chronicles the arduous efforts of American Catholics finally to have a saint from their own land. Along the way, she tells the story of an emerging church in the U.S., its relations with Rome, and how gender and power structures shaped this process.

On the eve of the feast day of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, one of the United States’s most notable homegrown heroes, Sprows Cummings spoke with The Tablet about the difficult journey to make their canonizations possible and the ongoing challenges of the sainthood process today.

The Tablet: Canonizations, you write, are about holiness – but not exclusively so. How, in your view, did the quest for an American saint help U.S. Catholics become Americans?

Sprows Cummings: When U.S. Catholics nominated their first candidates for canonization in the 1880s, most of their fellow citizens believed that Catholics’ religious loyalties prevented them from participating fully in American life. At the same time, many prelates at the Holy See doubted that Catholicism could flourish in a predominantly Protestant society. Saint seekers believed that canonizing an American would convince both U.S. Protestants and European hierarchs that Catholics belonged in America.

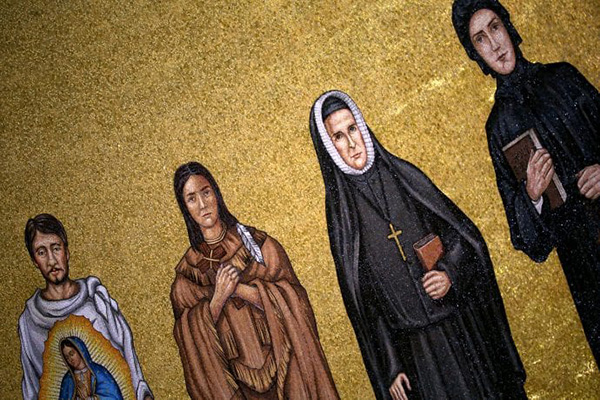

This strategy played itself out for over a century – and it ultimately succeeded. The 1946 canonization of Frances Cabrini, America’s first citizen saint, marked a pivotal moment, coinciding as it did with Catholics’ unprecedented integration into American life and their nation’s emergence as a global superpower.

Even more decisive were the canonizations of Elizabeth Ann Seton and John Neumann some thirty years later. By the time Seton and Neumann were elevated to the honors of the altar (in 1975 and 1977), respectively, there was no question that U.S. Catholics had gained influence in their church and consolidated their place in the nation.

You quote from mid-20th century poet Phyllis McGinley, who complains that the Vatican, in failing to name a U.S. saint, was overlooking the “very American brand of holiness.” Is there such a thing as an American brand of holiness?

Officially? Of course not. But the fact that U.S. saint-seekers saw themselves as chasing their very own national brand of holiness is what makes the story of canonization in America so interesting – and unique. U.S. Catholics belong to a church that moves slowly-this is especially true in the painstakingly sluggish process of canonization – but live in a culture that changes easily and rapidly. Even in the exceptional cases where a cause moved quickly in Rome, the interval between its beginning and its successful conclusion could seem an eternity when measured by U.S. standards.

New American moments generated new favorite saints, and in each new moment, U.S. Catholics spoke about their holy heroes in language that reflected not only sacred beliefs but the same secular developments – urbanization, industrialization, depression, war, global politics, or social and cultural change – that were shaping the lives of all Americans.

For a cause to succeed in Rome, U.S. Catholics had to make the case that prospective saints had practiced the theological and cardinal virtues: faith, hope, charity, prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice. For a cause to matter at home, U.S. Catholics had to believe that the candidates embraced American virtues and participated in American projects. You can see this in the outsize attention John Neumann’s promoters gave to his naturalization as a U.S. citizen, a footnote that carried zero weight at the Vatican. It’s also bizarre to hear church leaders like Cardinal Francis Spellman lionizing Elizabeth Ann Seton for being not only holy but “wholly American” – a “charter American citizen” who had “breathed American air” and exhibited “American stamina” and worked with “American efficiency.”

Do you buy the idea that these days, there’s hostility toward the American Catholic Church in Rome? And does this have any bearing on the canonization process?

I would characterize it less as “hostility” than as a stubborn perception that Rome doesn’t really understand the Church in the United States. This was certainly true in the early days of U.S. Catholics’ search for a saint of their own. The United States was classified as “mission territory” by the Vatican until 1908, and given that very few Roman prelates understood English, much about U.S. Catholicism was literally lost in translation at the Holy See.

And while there is a much greater understanding today, there are still many aspects of American life and culture that puzzle Vatican officials. I’d also say that the inverse is also true: most American Catholics don’t really grasp how Rome works. This leads to frustration and mistrust on both sides.

That said, I don’t think this mutual misunderstanding impacts canonization too much. Having witnessed many canonization Masses, I marvel at the emotion and energy that reverberates through the crowd when the pope names a new saint. At that moment, whatever dissatisfaction and discontent an individual feels toward the Church and its foibles and failings evaporates. All that matters is that the pope is declaring that a person close to you – a person who walked on the same soil you walk, who saw the same landscape – is in God’s eternal presence. It’s a magical moment.

You write about gender and power structures in the Church and the canonization process. How has this evolved and what work remains in the process in your view?

One fact that astonished me – and maybe it shouldn’t have – was that until very recently Catholic women could not represent themselves in causes for canonization. For most of church history, this was a matter of tradition, and it was theoretically possible for women to assert themselves in this way if they were brave and determined enough.

One of the most engaging stories I encountered was that of Mother Ellen McGloin, RSCJ, who seems to have spent two years acting as postulator for Philippine Duchesne in the 1890s. But the 1917 Code of Canon Law made the prohibition explicit, stipulating that women could petition for causes only through a male proxy designated by the Holy See.

Spiritual daughters of prospective female saints were thus forced to work through male mediators, many of whom, sad to say, were far more interested in their own glorification than that of the holy women they represented. The male proxy assigned to Elizabeth Ann Seton was particularly nefarious, and his meddling and mishandling stalled her cause for over twenty years and nearly derailed it entirely. It was only after his demise that Seton’s canonization was secured.

There is an irony in the fact that by the time the requirement for a male proxy was removed in 1983 (one of many changes to the process implemented by John Paul II) most U.S. Catholic women were eschewing canonization altogether. In the aftermath of Vatican II, many congregations of women religious were reluctant to devote time, personnel, and money toward pursuing causes, believing that doing so was not consonant with their renewed commitment to serving the poor.

For many sisters, the prospect of working closely with the hierarchy at every stage of the process also gave them pause. This is certainly true today, when many Catholic women, attuned to the gendered imbalance of power, resist interacting with the male hierarchy. In terms of canonization, Catholic women often worry that the stories of their beloved female heroes – many of whom led lives of radical holiness – will be co-opted by a church that recognizes all too few models of female sanctity.

Let’s talk money. Financial resources drive causes for canonization these days. How does that square with Pope Francis’s desire for a ‘poor Church for the poor’?

This is definitely a tension, but it is a tension that Pope Francis has the power to resolve. He could, for example, decentralize the process considerably by reverting to church tradition, and reserve canonization to the pontiff alone while permitting the local bishop to be the final judge on beatification. Such a change would certainly further Francis’s efforts to foster collegiality.

You briefly get into the controversy related to the tug-of-war between the archdiocese of New York and the diocese of Peoria over Fulton Sheen’s body. That’s been resolved, but his beatification has been indefinitely postponed over concerns that there needs to be more time to vet his record on handling abuse cases. What might the Sheen controversy teach us going forward about canonizing bishops or even popes in light of the clergy abuse scandals?

A central argument of “A Saint of Our Own” is that canonization reveals as much about the age in which candidates are proposed as it does about the age in which they lived. Whether we like it or not, this era of church history will be defined by the clergy sex abuse scandals. Very few men who served as bishops, cardinals, or even popes in the last sixty years will emerge with their legacy unscathed – and that includes Sheen.