By Rachelle Linner

(CNS) – Terrence Wright, an associate professor of philosophy and director of the pre-theology program at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary in Denver, wrote a well-intentioned introduction to Dorothy Day, setting out to rebut the false idea that she was a “dissenting Catholic.”

Her Fidelity To The Church

“Day never understood herself as a dissenter, and in my reading of her I had always been inspired by her fidelity to the church,” he writes. “I hope to show this faithfulness and dispel the mistaken view that she was, with one important exception, a dissenting Catholic. In her pacifism, Day clearly dissented from the teaching on what is known as the just-war theory, but she grounds this dissent firmly in Scripture.”

The book has many strengths. It begins with a concise overview of her childhood and early adulthood, her life as a radical journalist and relationship with Forster Batterham, the father of her daughter, Tamar. It was her joy over Tamar’s birth that led Day to become a Catholic and, several years later, her auspicious meeting with Peter Maurin led to the beginning of the Catholic Worker Movement.

The Catholic Worker

Wright offers a lucid explanation of the intellectual foundations of the Catholic Worker and the influences on Dorothy Day’s spirituality. He presents an excellent overview of the papal encyclicals “Rerum Novarum” (1891) and “Quadragesimo Anno” (1931) and the philosophy of French personalists Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier.

“The heart of personalism is the emphasis on the absolute value of every human person. This value … comes from his very existence as a human being made in the image and likeness of God.”

Liturgical and personal prayer were of central importance in Day’s life.

“She completely embraced the idea that what one does for those who suffer in these ways one does for Christ himself, and that when one ignores those who are suffering, one is ignoring Christ.”

Wright highlights the influence of Sts. Benedict, Francis of Assisi and Therese of Lisieux on the Catholic Worker’s understanding of hospitality, commitment to voluntary poverty, and perseverance in the way of hidden, daily service.

His long chapter on Day’s relationship with the Catholic Church (“not always an easy one; it was complex and at times paradoxical”) reads as a somewhat defensive apologetic.

He correctly notes “the influence of her contemporaries” Benedictine Father Virgil Michel and the liturgical movement and Father John Hugo, who led the Lacouture retreats.

But he ignores her many important relationships with people such as Trappist Father Thomas Merton, A.J. Muste and Jesuit Father Daniel Berrigan. He does not mention her work with Eileen Egan in establishing Pax Christi in the United States, although he does cite her presence at a prayer vigil in Rome in 1965, during the third session of the Second Vatican Council.

This chapter is the weakest in the book. Wright has the admirable intent of showing Dorothy Day’s loyalty, but he tries too hard to fit her into a preexisting model of sanctity.

Unfortunately, this diminishes many of her important contributions and ignores her distinctive American characteristics. Day was not just a loyal daughter of the church. Her spirituality and protest were formed and expressed at a particular time in American history.

To pretend otherwise is a disservice to her and to the reader of this otherwise fine book.

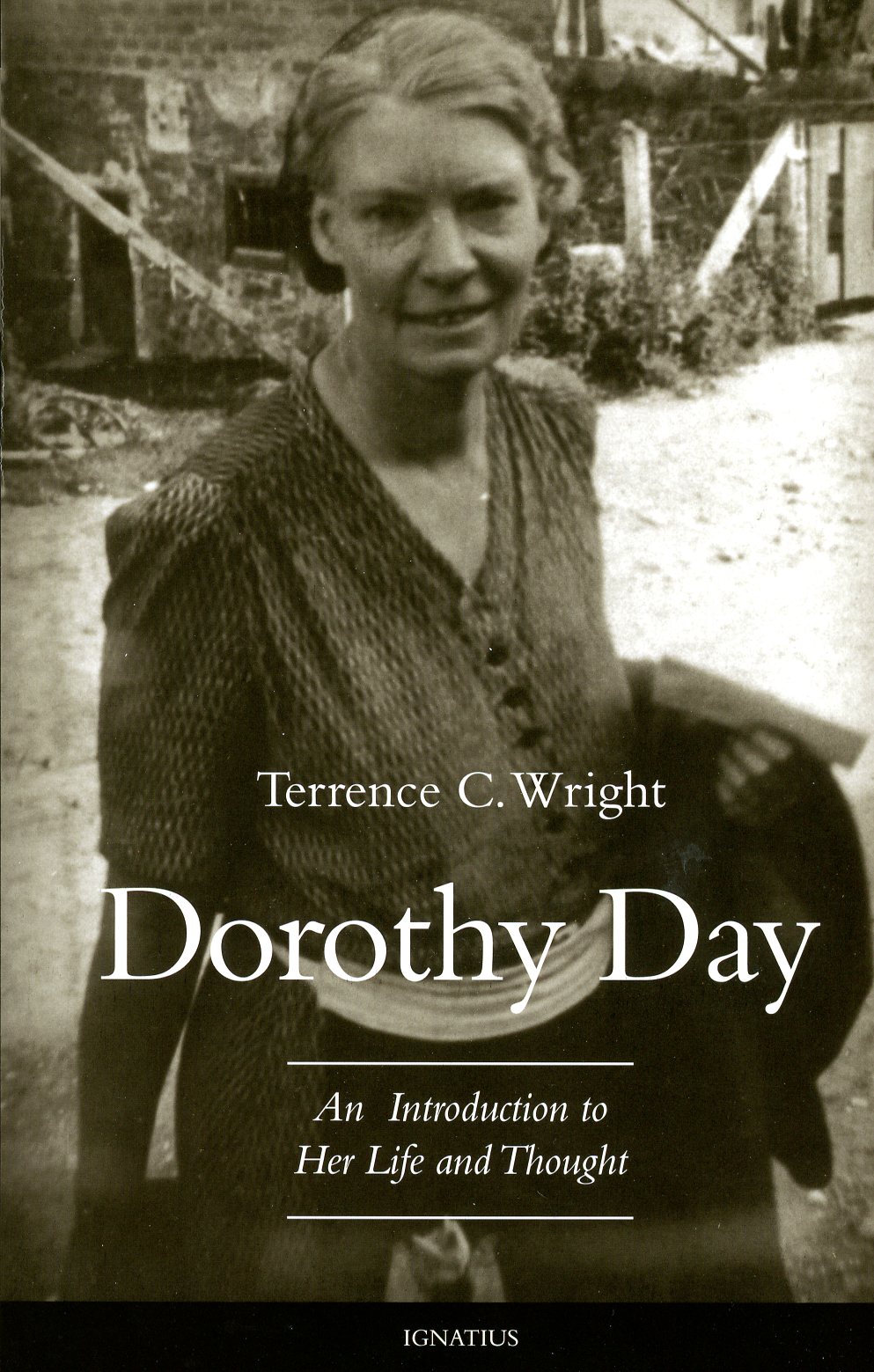

“Dorothy Day: An Introduction to Her Life and Thought,” by Terrence C. Wright.

“The Reckless Way of Love” is redeemed by its modest price and the pleasure of reading Day’s prose. Otherwise, it is a disappointing, sometimes frustrating book because no context is provided for any of the short (many just a paragraph) entries.

The editor has drawn from Day’s “On Pilgrimage” columns from the Catholic Worker newspaper, her classic books (“The Long Loneliness” and “Loaves and Fishes”) and two important volumes edited by Robert Ellsberg and published by Marquette University Press – “All the Way to Heaven,” her selected letters, and “The Duty of Delight,” her diaries.

The selections are organized thematically: the way of faith, of love, of prayer, of life, of community. Information about the source of a quote is found in a “Notes” section in the back of the book, but these lack dates or explanation of situation.

“The Reckless Way of Love” is an unfortunately sloppy book that diminishes the import of Day’s writing.

The interested reader would be better served by Ellsberg’s two volumes or by browsing the intelligent and well-maintained website of the Catholic Worker Movement at www.catholicworker.org.

“The Reckless Way of Love: Notes on Following Jesus,” by Dorothy Day, edited by Carolyn Kurtz.

Linner, a freelance writer and reviewer, has a master’s degree in theology from Weston Jesuit School of Theology.