In most sports, the amateur game in college is often similar to the same sport at the professional level. Hockey is still played on ice, football players all wear the same pads and the objective of putting the basketball into the hoop is the same on either a collegiate or professional court.

But in baseball, there is a stark difference between the college and professional level: college baseball players can still use aluminum bats.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) introduced aluminum bats in 1974 as a method to cut down on the costs of the large number of wooden bats that broke each season. At first, the difference was unnoticeable, until technological advances in the aluminum led to a new single-walled bat structure. These bats outperformed wood bats significantly.

However, the increased performance also led to a concern for player safety, especially for pitchers and infielders. With the ball jumping off an aluminum bat, a bad hop could potentially cost a player the rest of his career.

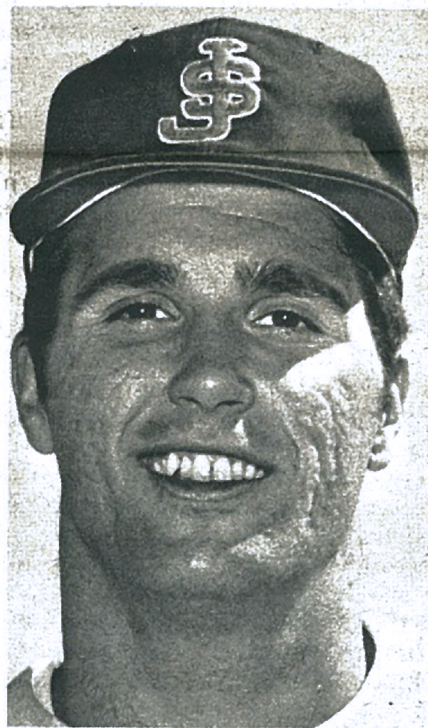

Former St. John’s University, Jamaica, catcher Ralph Addonizio is a supporter of re-instituting wooden bats in college. He’s seen the game played at all levels and realizes the impact the switch would have on the game.

“It really enlightens you on how the game can be played and should be played,” he said. “It puts the game in a different dimension.”

Addonizio grew up playing sandlot ball for St. Athanasius parish, Bensonhurst, before playing ball at St. Francis Prep, Fresh Meadows. Playing for the great coach Jack Kaiser at St. John’s, his teams reached the College World Series in 1966 and 1968 – the latter of which he served as team captain. Of course, he used wooden bats during his college days.

The Boston Red Sox drafted Addonizio in 1968. Though he never received the call to the big leagues, he’s been around the game of baseball ever since his playing career ended. He is currently the commissioner of the Atlantic Collegiate Baseball League (ACBL), one of eight MLB-sanctioned summer leagues to keep college players fresh during the off-season.

Many of these summer leagues, including the ACBL, use wood bats. However, when the players return to their school teams in the fall, they go right back to using aluminum bats.

“Can you think of any sport in which you take the offensive weapon and change it when you go on to play at the professional level?” Addonizio said. “The only one that does it is baseball.”

In 1986, the NCAA imposed a lower weight limit on aluminum bats in an attempt to decrease the impact of when a player made contact. Bat speed increased, but since the bat itself was lighter, collective offensive numbers declined over the next few seasons.

However, many NCAA offensive records were shattered during the 1998 season, which forced the organization to take action once more. The Ball-Exit-Speed Ratio (BESR) was developed to regulate the performance of aluminum bats. The “minus-3” rule was also adopted in which a bat’s length in inches could only exceed its weight in ounces by three digits.

Safety was once again the main concern of the NCAA. But if that’s the case, why not just switch back to wood? The hitting area of a wooden bat is much smaller than that of an aluminum bat, so the odds of squaring up a pitch perfectly decrease with wood.

In 2006, the N.Y. CHSAA switched to wood bats. Though many players were forced to switch midway through their high school careers, the games became safer and more realistic, rather than having exorbitant run differentials.

“You’re playing 10-run games,” Addonizio said. “Baseball is not a game that’s played by scoring that many runs. It’s a game of pitching and defense.”

In addition to safety and lower-scoring games, the argument of preparation for college players has the most substance in switching permanently to wooden bats. According to the NCAA, 9.1% of college baseball players become professionals – the highest of any college sport. Yet, the vast majority of these players fizzle out because they can’t adjust to the wood bats.

As such, the current MLB Draft system is really a shot in the dark. Because college players have used aluminum their whole lives – even if they play in the wood-bat summer leagues – it’s difficult to determine how their game will translate to the next level.

“If you’re a player using a metal bat, you wind up with coaches teaching you how to hit with a metal bat, which is certainly different from how you hit with a wood bat,” Addonizio said. “When you make the adjustment to wood, you recognize just how far behind the curve you are.”

Just recently, the NCAA again altered its bat standards. The average amount of home runs per game increased from 0.68 in 2007 to 0.84 in 2008 and to 0.96 in 2009.

Starting in spring 2011, all college teams became required to use bats that meet the “Bat-Ball Coefficient of Restitution” (BBCOR) standard. The goal was to have the bats produce a similar effect to wooden bats.

With these BBCOR bats, the “ping” of a regular aluminum bat has become a thing of the past. The contact of bat to ball produces more of a deadening sound.

The BBCOR formula measures the amount of energy lost at impact. The more energy that is lost at impact, the slower the speed that the ball will jump off the bat. With BESR bats, a “trampoline effect” results causing the ball to depress and then return to its original position.

Still, a BBCOR bat is an aluminum bat and thus differs from the pro game.

“It’s a totally different game,” Addonizio said. “If you’re using wood at the professional level, how can you be teaching with metal? I’m not a proponent of metal.”

Unfortunately, it may take another serious injury caused by an aluminum bat for the NCAA to explore the possibility of wood. But for now, the sponsorships the organization receives from bat companies seem to trump the players’ safety.

North Americans Win Clericus Cup

ROME (CNS) – For the first time, the Pontifical North American College took home the champion’s title in the Clericus Cup soccer series.

To the cheers of superheroes and other fans in the stands, the NAC Martyrs beat last year’s champions, the Pontifical Gregorian University, 3-0, in the final playoff May 12.

“We pretty much controlled the entire game. There was no risk of conceding a goal and as long as the offense did their job,” the final win was in the bag, third-year seminarian John Gibson of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee told Catholic News Service.

Gibson scored two goals in the first half and Scottie Gratton of the Diocese of Burlington, Vt., netted the final goal. Playing for the Martyrs, Lewi Barakat of the Archdiocese of Sydney provided all three assists in the game.