April 21 marked the one-year anniversary of Major League Baseball’s agreement on a new plan to pay life annuities to men who weren’t originally eligible to receive pensions. After years of waiting, hundreds of former players who didn’t qualify for any retirement benefits were finally rewarded by the league for their contributions to the national pastime.

But is this new system enough to downplay the years of suffering many of these players endured?

According to the agreement between MLB and the MLB Players Association, ballplayers who played between 1947 and 1979 will receive as much as $10,000 annually, depending on their service time and accomplishments in the game.

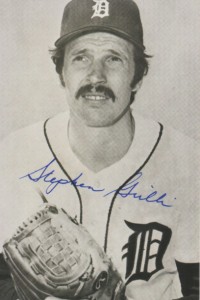

One of these players is Steve Grilli, a native of Cypress Hills who attended St. Rita’s parish, East New York. Grilli signed with the Detroit Tigers in 1970 and spent two and a quarter years in the big leagues. He pitched in 147.2 innings over 69 career games.

By today’s standards, Grilli would have certainly qualified for both the MLB pension and full health insurance. In order to avoid a players strike in 1980, MLB and the players union agreed on a new pension system that gave health insurance to any player that appeared in just one game and a full pension to players on a Major League roster for at least 43 days – one quarter of a season.

Based on this system, Grilli would have received upwards of $30,000 each year upon his retirement in addition to full medical coverage. However, Grilli’s career was over before 1980, and thus he was affected by the old system.

Before 1980, a player had to have at least four years of service time at the Major League level to qualify for a pension. If not, that player received no monetary compensation or health insurance.

Ironically, though Grilli received nothing, his son Jason – a 10-year MLB veteran currently pitching with the Pittsburgh Pirates – would have received a full pension in accordance with the new system.

Jackson Heights native and journalist Doug Gladstone realized this inequity. He works as an assistant public information officer for the N.Y. Retirement System, so he is familiar with issues regarding vesting and pension eligibility.

While working on a story for Baseball Digest about the 40th anniversary of New York Mets pitcher Tom Seaver’s “Imperfect Game” of 1969, Gladstone interviewed the man who broke up Seaver’s perfect-game bid: Chicago Cubs rookie outfielder Jimmy Qualls. Qualls mentioned that he received nothing from MLB, which sparked Gladstone to launch a crusade to help these forgotten ballplayers.

“I truly believe that our children are our future, but I also believe that we owe it to those who came before us to show them a little healthy respect,” Gladstone said.

On April 14, 2010, Gladstone’s book entitled “A Bitter Cup of Coffee: How MLB & The Players Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve” was released. Gladstone profiles 40 of these 874 former big leaguers, including Grilli, who didn’t qualify for the new pension system.

“He’s (Gladstone) put it on the table like it’s supposed to be,” Grilli said.

Of the 40 players Gladstone spoke to, only one – a former St. Louis Cardinals pitcher named Dan O’Brien – said that he did not want a pension from MLB. O’Brien, who appeared in 13 games from 1978 to 1979, knew what the rules were during the time he played, and therefore he feels he does not deserve the benefits of the new agreement.

Gladstone said he was elated that, based on the April 21, 2011 agreement, these players would at least be getting something for their service time in baseball. However, he called the agreement “only a partial victory,” though he said that legally, MLB does not have to do anything.

“MLB has done something, but in my opinion, they haven’t done nearly enough for these men,” Gladstone said. “It’s better than what some of these men were getting, which was obviously nothing, but MLB could do more. The players’ union could do more, and they should do more.”

Under the new terms, these players cannot buy into the league’s health insurance policy, and the payments they receive are a life annuity – meaning the payments stop once the player passes away rather than be forwarded to a designated beneficiary.

Grilli called the new life annuity plan “not life-altering” by any means. He has received his first two payments of $5,000, which becomes roughly $3,900 after taxes. These payments will continue until at least 2016 when the league’s collective bargaining agreement expires.

Grilli said he’s lucky to be at the end of the spectrum in that his career officially ended in 1979, less than a year before the current pension system was implemented. He can only imagine the struggles in which players who retired in the 1950s or 1960s were forced to face.

“When you see how the league has taken care of everyone else, I just can’t understand why they haven’t reached out to us forgotten ballplayers,” Grilli said.

Gladstone said he hopes someday that this group of players will be fully included in the league’s pension coverage. He said this is a moral issue more so than a legal issue in that it’s a social injustice that hasn’t been remedied properly.

“The league, the union and especially the Major League Baseball Alumni Association have all…you’ll to pardon the pun… dropped the ball,” Gladstone said.

Though today Grilli is doing just fine as the television color commentator for the Syracuse Chiefs – the Triple-A affiliate of the Washington Nationals – he’ll always be remembered as one of baseball’s “forgotten boys.”

Consecutive Perfect Games for St. Joe’s Ace

St. Joseph’s College’s Brooklyn Campus, Clinton Hill, senior softball pitcher Alyson Chiaramonte had quite a weekend April 13-15.

She wasn’t superstitious at all as she threw a five-inning perfect game on Friday the 13th in St. Joe’s 14-0 win over Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, N.Y.

Chiaramonte followed up that effort two days later with another perfect game – this time a seven-inning 6-0 shutout of John Jay College, Philadelphia, Pa. She struck out 10 batters and rendered 11 outs via the ground ball.

The two perfect games came as part of the Lady Bears 15-game winning streak that matched the longest in program history (2003).