PROSPECT HEIGHTS — Father Marcel Uwineza recalls he was 14 in April 1994 when a fearful pall “like an evil spirit” draped his hometown in the East African nation of Rwanda.

His family were Tutsi, a rival tribe of the majority Hutus in a struggle for political power and economic opportunities.

In 1990, a Tutsi rebel army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, launched a civil war. President Juvénal Habyarimana signed a peace accord with them in 1993, which angered his fellow Hutus.

His plane mysteriously exploded on April 6, 1994. The Hutu accused the Tutsi of assassination, and thus began the Rwandan genocide.

Father Uwineza said the Hutu had spent months openly preparing for the slaughter. United Nations observers also anticipated trouble, but the organization did little to intervene.

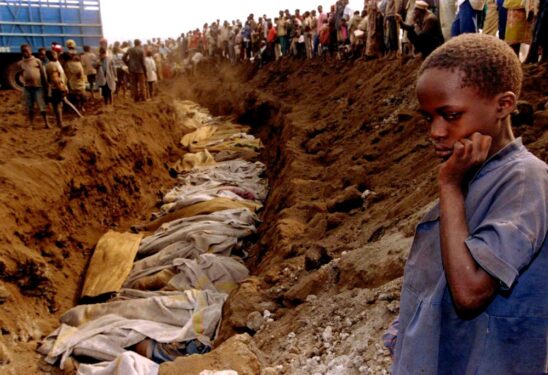

“Machetes were distributed among our neighbors,” Father Uwineza said. “They dug holes where people would be thrown.”

So Fast, So Violent

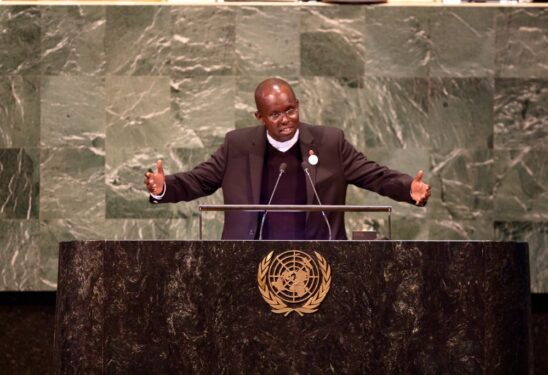

Father Uwineza, a Jesuit, is president of Hekima University College, a Catholic institution in Nairobi, Kenya.

He is also a theologian. He wrote three books on the genocide, including “Risen from the Ashes: Theology as Autobiography.”

But as a teen, he angrily blamed Church leaders who were involved in the genocide. About 800,000 men, women, and children, including much of his family, perished.

“Rwanda really stands out,” said Fred Cocozzelli, a political science professor at St. John’s University, who lectures on genocide. “It was just so fast, so intense, and so violent.”

Common Language

Hutu and Tutsis share similarities, said J.J. Carney, professor of theology and African Studies at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska.

For example, both speak Kinyarwanda, a Bantu dialect.

The Hutu became farmers, while the Tutsi chose more profitable cattle raising. Greater wealth brought political power, Carney said.

“Even prior to the arrival of Europeans around 1900, there was growing tension between a ‘royal court’ that became increasingly Tutsi-dominated,” Carney said.

Doubled Down

The colonial government of Belgium “doubled down on that system,” so that minority Tutsi benefited the most from colonial government services and schools, Carney said.

But, later, the Belgians and supportive Catholic missionaries abruptly favored the Hutu in order to govern with the majority group’s support.

Consequently, the groups began fighting in 1959. Violence grew when civil war erupted in 1990.

Cocozzelli said Hutu leaders moved to crush the Tutsi. Dehumanizing rhetoric spewed from state-run radio, often calling the Tutsi “cockroaches,” he said.

Hutu partisans bought into the message and sharpened machetes.

Pit Latrine

On April 6, 1994, Father Uwineza was on spring break at his Ruhango-district home. His mother was the only parent.

His father, a tailor, died two years prior in a Hutu attack. They falsely claimed he supported the RPF, Father Uwineza said.

The future priest’s two young brothers and a sister — ages 7, 5, and 3 — were visiting an aunt in the capital city, Kigali, when the killings began. A brother of the aunt’s housekeeper murdered them, Father Uwnieza said.

“He threw their bodies into a pit latrine,” he said, “(where) people go to the toilet.”

A Serious Hatred

Father Uwineza and his mother fled to a parish in another district, but the pastor refused protection.

Father Uwineza was horrified; 70% of Rwandans were Catholic — both Tutsi and Hutu. How could a priest deny safety?

History shows that while many priests were complicit in the slaughter, some joined further — like a pastor who reportedly ordered the bulldozing of church property where Tutsi people hid.

Father Uwineza recalled his first Communion in 1988; he received the host and suddenly wanted to be a priest. That changed as he trudged from the sealed-off parish.

“I developed a serious hatred for leaders of the Church,” Father Uwineza said.

Militiamen fatally beat Father Uwineza’s mother, but a beekeeper hid him among the hives. Eventually he reached a refugee camp.

The Desire Came Back

The genocide ended in July 1994, concurrent with the RPF’s civil war victory.

The Tutsi, still the minority, have since controlled the government and the military.

Father Uwineza said an uncle exiled in Burundi returned to raise him, and ensure he attended Mass, despite his anger.

“I went to Mass, not out of love for God, but out of fear of my uncle,” he said. “But that’s where God caught me.”

He went to a Jesuit parish in downtown Kigali where priests projected a down-to-earth nature, even though they, too, suffered in the genocide.

About 200 Catholic priests and nuns died in the slaughter. But the Jesuits sought inner peace through forgiving the attackers — an example that softened Father Uwineza’s heart.

“The desire I had came back,” he said. “I wanted to be a priest.”

I Felt Free

Father Uwineza was not yet ordained in 2003 when he visited his family’s burial plot. Suddenly, the man who murdered his young brothers and sister appeared.

“I felt there was a monster before me,” he said of the man, who had been released from prison. “Then he said, ‘Would you have some space in your heart to forgive me?’”

After a moment of confusion, Father Uwineza felt a power “invade” him. He wanted to forgive the man, and did.

“When we finally embraced, I felt as if there were chains cut from my legs,” he said. “I felt free.”

Forgive Us for Hate

On Nov. 21, 2016, bishops in the Catholic Episcopal Conference of Rwanda issued a statement that coincided with the formal end of the “Holy Year of Mercy” declared by Pope Francis.

“We apologize for all the wrongs the Church committed,” they wrote. “Forgive us for the crime of hate in the country to the extent of also hating our colleagues because of their ethnicity.

“We didn’t show that we are one family but instead killed each other.”

Pope Francis, in 2017, issued his own apology about the genocide, saying it, “disfigured the face” of the Roman Catholic Church.